Kitt Peak Nightly Observing Program

Splendors of the Universe on YOUR Night!

Many pictures are links to larger versions.

Click here for the “Best images of the OTOP” Gallery and more information.

Big Dipper

The Big Dipper (also known as the Plough) is an asterism consisting of the seven brightest stars of the constellation Ursa Major. Four define a “bowl” or “body” and three define a “handle” or “head”. It is recognized as a distinct grouping in many cultures. The North Star (Polaris), the current northern pole star and the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper, can be located by extending an imaginary line from Big Dipper star Merak (β) through Dubhe (α). This makes it useful in celestial navigation.

Little Dipper

Constellation Ursa Minor is colloquially known in the US as the Little Dipper, because its seven brightest stars seem to form the shape of a dipper (ladle or scoop). The star at the end of the dipper handle is Polaris, the North Star. Polaris can also be found by following a line through two stars in Ursa Major—Alpha and Beta Ursae Majoris—that form the end of the ‘bowl’ of the Big Dipper, for 30 degrees (three upright fists at arms’ length) across the night sky.

Summer Triangle

The Summer Triangle is an asterism involving a triangle drawn on the northern hemisphere’s celestial sphere. Its defining vertices are the stars Altair, Deneb, and Vega, which are the brightest stars in the constellations Aquila, Cygnus, and Lyra, respectively.

Teapot and Teaspoon

The brightest stars in the zodiac constellation Sagittarius form the shape of a teapot, complete with lid, handle, and spout. The plane of the Milky Way runs through Sagittarius, and just over the spout and lid of the teapot, making it look as if steam is rising from the spout of the teapot. The center of our Milky Way galaxy is in the direction of this starry steam. If you look above the handle of the teapot, you might spot a teaspoon.

The Coathanger

Also called Cr 399, or Brocchi’s Cluster, this group of stars might remind you of a closet. The stars that make up The Coarhanger are not a part of a cluster, but instead, have randomly arranged themselves in a coathanger-like shape. Chaotic stellar orbital motion can sometimes make interesting shapes!

Andromeda

Andromeda was the princess of myth who was sacrificed by her parents to the sea monster Cetus. Fortunately, the hero Perseus came along to save her, and they were eventually married. The constellation Andromeda is host to the Andromeda Galaxy. Although there are smaller, dwarf galaxies that are closer to our galaxy, Andromeda is the closest big galaxy like our own; in fact, it’s bigger.

Aquarius

Aquarius, the water-carrier is said to resemble a figure carrying a jug of water. This aquatic constellation is one of the zodiac constellations, so the planets, Sun, and Moon move across its boundaries. Aquarius and other nearby aquatic-themed constellations make up a region of the sky known as “the Sea”.

Aquila

The brightest star in Aquila is Altair—one of the brightest starts in the summer sky, and a point of The Summer Triangle. The name aquila is latin for eagle, and the brightest stars in this constellation do seem similar to the shaape of an eagle standing upright with its wings spread out at its sides. Altair is at the head, or more precisely, the eye of the eagle. In Greek mythology, Aquila carried Zeus’s thunderbolts.

Aries

Aries is a medium-brightness constellation, but with few stars and an indistinctive shape, which makes it more challenging to recognize.

Auriga

Auriga is located north of the celestial equator. Its name is the Latin word for “charioteer”, associating it with various mythological charioteers, including Erichthonius and Myrtilus. Auriga is most prominent in the northern Hemisphere winter sky, along with the five other constellations that have stars in the Winter Hexagon asterism. Auriga is half the size of the largest constellation, Hydra. Its brightest star, Capella, is an unusual multiple star system among the brightest stars in the night sky. Because of its position near the winter Milky Way, Auriga has many bright open clusters within its borders, including M36, M37, and M38. In addition, it has one prominent nebula, the Flaming Star Nebula, associated with the variable star AE Aurigae.

Capricornus

This faint zodiac constellation’s name means “horned goat”, and is often depicted as not only a goat, but a sea-goat. It’s faint and hard to spot, but is roughly triangular-shaped. Zodiac constellations are the constellations along the ecliptic—the plane of the Solar system. This means planets pass through Capricornus from time to time.

Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia is widely recognized by its characteristic W shape, though it may look like an M, a 3, or a Σ depending on its orientation in the sky, and your position on Earth. However it’s oriented, once you’ve come to know its distinctive zig-zag pattern, you’ll spot it with ease. The plane of the Milky Way runs right through Cassiopeia, so it’s full of deep sky objects—in particular, a lot of open star clusters. Cassiopeia is named for the queen form Greek mythology who angered the sea god Poseidon when she boasted that her daughter Andromeda was more beautiful than his sea nymphs.

Cepheus

King Cepheus from Greek mythology was husband to Cassiopeia and father of Andromeda. The brightest stars in the constellation Cepheus seem to form a kind of crooked house, with the roof pointing to the North. this constellation is very near the Celestial North Pole, so it’s not visible from the Southern Hemisphere. The star Delta Cephei was the first ever identified cepheid variable star, a very important kind of variable stars that helps astronomers determine distances to nearby galaxies.

Cetus

Though it’s often called “The Whale”, Cetus is named for the terrible sea monster from Greek mythology who was slain by Perseus as he rescued the Princess Andromeda who had been sacrificed to appease the wrath of the sea god Poseidon. The constellation Cetus is in the southern sky, just south of the zodiac constellation Pisces.

Corona Borealis

Corona Borealis, or “Northern Crown”, is a tiara-shaped, or C-shaped constellation. Its brightest star, called Alphecca, or Gemma, shines like the crown jewel centerpiece of a brilliant celestial tiara. It’s southern counterpart, Corona Australis, or “Southern Crown” lies just south of the ecliptic.

Cygnus

Cygnus is a large constellation, prominent in the Northern Hemisphere. Its name comes from the Greek for “Swan” and can be imagined as a giant, celestial swan, flying overhead, with its wings fully extended. The brightest star in Cygnus is Deneb, which is one of the brightest stars in the sky, and a whopping 800 lightyears away! Deneb is one point of an asterism called the Summer Triangle—three very bright stars that form a large triangle shape prominent in the Northern hemisphere summer skies.

Draco

Draco the dragon lies close to the North polar point of the celestial sphere. Thus, it is best viewed from north of the equator. This celestial dragon has a long serpentine shape that winds around the constellation Ursa Minor (better known by the name Little Dipper), which is far fainter than it’s companion, Ursa Major. The tail of Draco separates these two constellations.

Hercules

Hercules is named for the famous hero of Greek mythology by the same name. It’s one of the larger constellations, but its stars are of only moderate brightness. The Keystone is a well known trapezoid-shaped asterism (association of stars that are not an official constellation) within Hercules. This constellation is host to M13 (Messier 13), a globular star cluster. Otherwise known as the Hercules Globular Cluster, M13 is home to 300,000 stars, and is just over 22,000 light-years away.

Lyra

Lyra is a small, but notable constellation. It is host to Vega—the fifth brightest star in the sky (or sixth, counting the Sun). Not far from Vega is Messier object 57—the Ring Nebula, which is perhaps the best known planetary nebula in our sky. Lyra’s name is Greek for lyre—a kind of harp.

Ophiucus

The name Ophiucus comes from Greek and means serpent-bearer. This constellation goes hand-in-hand with the constellation Serpens—a constellation that is uniquely divided into two parts, the head and tail of the serpent, on either side of Ophiucus. The ecliptic actually runs through the very southernmost part of the area of sky defined as this constellation, making it—technically—a zodiac constellation.

Pegasus

This constellation is named for one of the most beloved creatures of Greek mythology—the winged horse named Pegasus. Within Pegasus is a well known asterism containing the 3 brightest stars in the constellation (+ 1 in Andromeda) called The Great Square of Pegasus. Alpheratz, the brightest star in the square, actually belongs to the constellation Andromeda, but in the past, this star had been considered to belong to both constellations.

Perseus

Hero of Greek mythology, Perseus is the character who slayed Medusa and rescued the Princess Andromeda from the sea monster Cetus. This is why you will find the constellations Andromeda, Cetus, and Andromeda’s parents Cassiopeia and Cepheus, nearby each other in the sky. Perseus’s brightest star is called Mirfak (Arabic for elbow). The plane of the Milky Way runs through Perseus, so there are many deep sky objects to be found.

Pisces

Pisces, the fish, is a faint, roughly V shaped constellation. It has been depicted as two fish tied to the ends of a rope (or cord) which is bent into a V shape. None of the stars in Pisces are particularly bright, or well known, but occasionally, bright planets pass through Pisces as they follow the path of the ecliptic (the plane of the Solar System) across the sky. This is why Pisces is well known despite being faint—it’s a zodiac constellation.

Sagittarius

Sagittarius, the archer, is often depicted as a centaur wielding a bow and arrow. Within Sagittarius, is a fairly recognizable teapot shape known to many simply as The Teapot (the teapot is not a true constellation, but an asterism). The plane of the Milky Way passes through Sagittarius, and in fact, the center of the Milky Way is in the direction of the westernmost edge of this constellation—just above the spout of The Teapot. With the plane of the Milky Way passing through, there are a plethora of deep sky objects to be found in Sagittarius.

Scorpius

Both the plane of the Solar System (called the ecliptic) and the plane of the Milky Way pass through Scorpius—the scorpion. As a result, you can find both the planets of our Solar System (which move along the ecliptic), and many kinds of deep sky objects in this constellation. Scorpius’s brightest star, Antares, is also known as the Heart of the Scorpion, because of it’s reddish hue and location in the chest of the scorpion. Being both red in color, and near the ecliptic, Antares is a rival of sorts to the planet Mars, which is also reddish in color, and occasionally passes through Scorpius. The name Antares means “opposing Mars”.

Sculptor

Sculptor is a faint constellation best seen from the Southern Hemisphere. The Sculptor Galaxy lies just within the northern boundary of the constellation—an exciting binocular or telescope object almost visible to the naked eye.

Triangulum

Triangulum is a small and simple constellation, and perhaps the only constellation that truly looks like its namesake—a triangle. Within the boundaries of the constellation lies one of our nearest neighbor galaxies—a galaxy known as the Triangulum Galaxy (Messier 33). At only 3 million light-years away, Triangulum is one of our closest neighbors.

Ursa Major

Ursa Major, or, the Big Bear, is one of the best known and most well recognized constellations, but you might know it by a different name. Contained within the boundaries of the constellation Ursa Major is the Big Dipper, which is not a true constellation, but an asterism. The Big Dipper is useful for finding both the North Star and the bright star Arcturus. Follow the curve of the handle to “arc to Arcturus” and use to two stars in the dipper opposite the handle to point to the North Star.

Ursa Minor

Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, is much fainter than it’s companion the Big Bear, Ursa Major. Within Ursa Minor is the well known asterism The Little Dipper. The end of the tail of the bear, or the end of the handle of the dipper, is a star called Polaris—the Pole Star, or the North Star. This special star happens to sit at the point where the Earth’s axis of rotation intersects the sky

M17 Swan Nebula

M17, also known as the “Swan Nebula,” or the “Omega Nebula” is a vast cloud of gas—mostly hydrogen, in which clumps of gas are contracting to make new stars. The nebula is 15 light-years across, and 5,500 light-years away.

M20 Trifid Nebula

M20, the “Trifid Nebula” gets its nickname from the dark dust lanes that seem to split it into three parts. It is a region of star formation—a giant cloud of gas, roughly 30 light-years across, and about 5,200 light-years away.

M8 Lagoon Nebula

M8: The “Lagoon Nebula.” A huge cloud of gas and dust beside an open cluster of stars (NGC 6530). The Lagoon is a stellar nursery, 4,100 lightyears away, towards the galactic core.

M31 Andromeda Galaxy

The Andromeda Galaxy is our nearest major galactic neighbor. It is a spiral galaxy 2,500,000 light-years away, and has a diameter of 220,000 light-years. This galaxy contains as much material as 1.5 trillion suns.

M32 Smaller Satellite of Andromeda

M32 is a small, but bright companion galaxy to M31. It orbits M31 much like the Moon orbits the Earth. It lies at the same distance as M31 but is much smaller (6,500 light-years across).

M13 Hercules Globular

M13, the “Great Globular Cluster in Hercules” was first discovered by Edmund Halley in 1714, and later catalogued by Charles Messier in 1764. It contains 300,000 stars, and is 22,000 light-years away. Light would need over a century to traverse its diameter.

Ecliptic

The ecliptic is a path in the sky, forming a great circle around the Earth, which the Sun and other planets of the Solar System move along. It is formed where the plane of the Solar System intersects with the Earth’s sky.

Meteors

Quick streaks of light in the sky called meteors, shooting stars, or falling stars are not stars at all: they are small bits of rock or iron that heat up, glow, and vaporize upon entering the Earth’s atmosphere. When the Earth encounters a clump of many of these particles, we see a meteor shower lasting hours or days.

Milky Way

That clumpy band of light is evidence that we live in a disk-shaped galaxy. Its pale glow is light from about 200 billion suns!

Satellites

Human technology! There are almost 500 of these in Low Earth Orbit (we can’t see the higher ones). We see these little “moving stars” because they reflect sunlight.

Scintillation

The twinkling of star light is a beautiful effect of the Earth’s atmosphere. As light passes through our atmosphere, its path is deviated (refracted) multiple times before reaching the ground. Stars that are near to the horizon will scintillate much more than stars high overhead since you are looking through more air (often the refracted light will display individual colors). In space, stars would not twinkle at all. Astronomers would like it if they could control the effects of this troubling twinkle.

Double Cluster

The “Double Cluster” (NGC 884 and NGC 869) is a pair of two open star clusters that are a treat for binoculars and telescopes alike. Each is a congregation of many hundreds of stars, around 50-60 light-years in diameter. These clusters are both about 7,500 light-years away.

Hyades

The Hyades is the nearest open star cluster to the Solar System at about 150 light-years away and thus, one of the best-studied of all star clusters. It consists of hundreds of stars sharing the same age, place of origin, chemical content, and motion through space. In the constellation Taurus, its brightest stars form a V shape along with the brighter red giant Aldebaran, which is not part of the cluster, but merely lying along our line of sight. The age of the Hyades is estimated to be about 625 million years. The cluster core, where stars are most densely packed, has a diameter of about 18 light-years.

M11 Wild Duck Cluster

M11 is an open star cluster also known as the “Wild Duck Cluster,” due to its purported prominant V-shape, reminiscent of a flock of wild ducks in flight. This open cluster is 20 light-years in diameter and 6,200 light-years away.

M45 The Pleiades

M45, the “Pleiades,” is a bright, nearby star cluster, in the last stages of star formation. About seven stars stand out as the brightest in the cluster, and is why the cluster is also known as the “Seven Sisters,” alluding to the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters from Greek mythology. In Japanese, the cluster is known as “スバル,” “Subaru,” and is featured as the logo of the automobile manufacturer of the same name. The Pleiades lies about 440 light-years away and is a very young (for an open star cluster) 100 million years old.

M6 The Butterfly Cluster

M6, the “Butterfly Cluster” is an open star cluster, located near the tail of Scorpius, next to another open cluter: M7. Containing a few hundred stars, it is smaller than neighbor cluster M7, at about 12 light-years across, and is 1,600 light-years away.

M7 Ptolemy Cluster

M7, also known as the “Ptolemy Cluster” is an open star cluster near the “stinger” of Scorpius. It is a group of suns in a gravitational dance, 25 light-years across and about 1,000 light-years away.

M57 Ring Nebula

M57: The Ring Nebula. This remnant of a dead star looks exactly as it’s name says – a ring or doughnut shape cloud of gas. The nebula is about 2.6 lightyears across and lies about 2,300 lightyears away.

M76 Little Dumbbell Nebula

M76: “The Little Dumbell”. This complex bubble of gas is the cloud of material ejected by a dying star. This ghostly glow has a fairly bright rectangular component with very dim outer loops. M76 is estimated to be more than 2,500 light years away; which means the bubble of gas is more about 1.2 light years across.

Jupiter

Jupiter is the largest planet in the Solar System, a “gas giant” 11 Earth-diameters across. Its atmosphere contains the Great Red Spot, a long-lived storm 2-3 times the size of the Earth. The 4 large Galilean satellites and at least 63 smaller moons orbit Jupiter.

Saturn

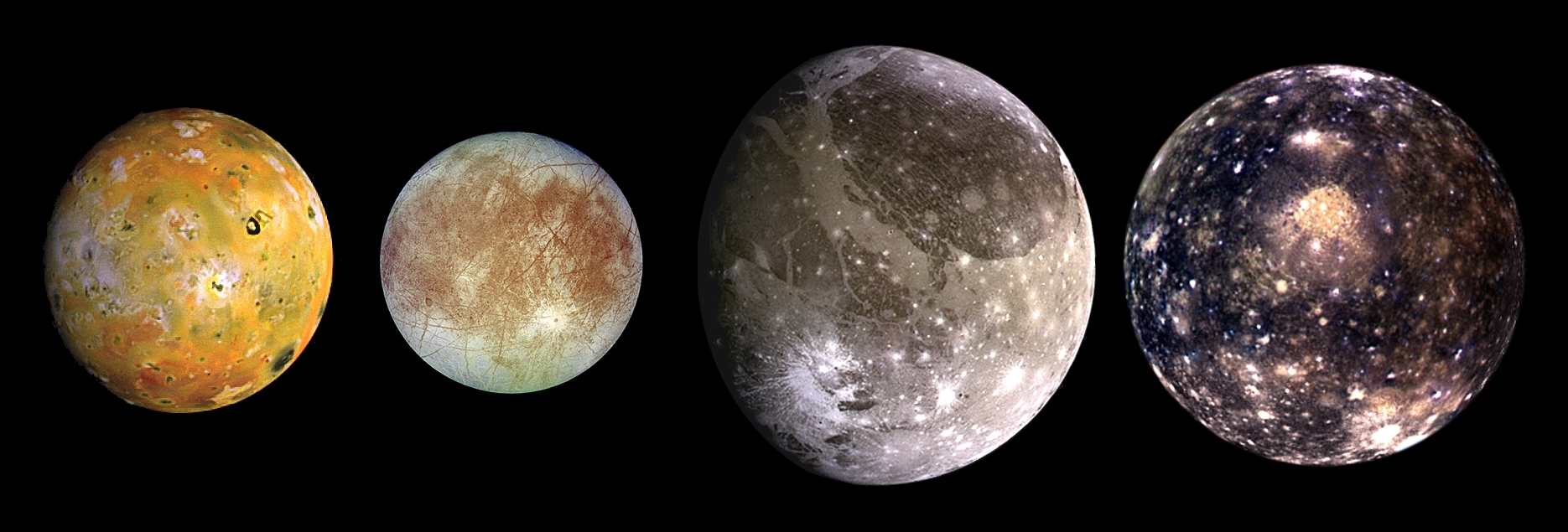

The Galilean Moons

Jupiter’s four largest moons are known as the Galilean Moons, named for Galileo, who was the first astronomer to study them in depth and determine that they were orbiting Jupiter. Their individual names are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—in orbital order from closest to Jupiter to furthest out. Ganymede is the largest of these four moons, and is the largest moon in our Solar System. Io, the closest of these four moons to Jupiter, is the most volcanic world in our Solar System. Io is home to hundreds of active volcanos. Its neighbor, and the next furthest from Jupiter of the four, Europa, is a dramatic contrast to Io with its icy surface. Europa is covered by water, which is frozen solid at the surface. The furthest our of the four, Callisto is a fascinating world in our Solar System because it is so utterly geologically dead. Without weather, moonquakes, volcanism, or any other surface-altering processes, Callisto’s surface is billions of years old—a kind of record of the history of the Solar System.

Uranus

51 Pegasi/Helvetios

51 Pegasi is a Sun-like star located about 50 lightyears from Earth. The 51 Pegasi system is home to the first exoplanet to ever be discovered, known as 51 Pegasi b or Dimidium. 51 Peg b is a large planet, about half the mass of Jupiter, orbiting very close to its parent star. The star 51 Pegasi can actually be seen with the naked eye under fairly dark skies.

61 Cygni

61 Cygni is a binary star system in the constellation Cygnus consisting of a pair of K-type stars, similar to each other in radius, mass, and brightness. The pair orbit each other in a period of about 659 years. This binary system can be seen with the naked eye in areas with low light pollution. 61 Cygni became of interest to astronomers in the early 19th century when its large proper motion was discovered—meaning its position moves slightly respective to the other stars around it. 61 Cygni currently has the highest proper motion among naked-eye visible stars. The distance to stars with large proper motion can be measured using the parallax method, and 61 Cygni became one of the first stars to have its distance measured.

Albireo (β Cyg)

Named long before anyone knew it was more than one star, Albireo (β Cygni) comprises of a set of stars marking the beak of Cygnus, the swan. Through a telescope, we see two components shining in pale, but noticeably contrasting colors: orange and blue. The difference in color is due to the stars’ difference in temperature of over 9000°C! The brighter orange component, Albireo A, is actually a true binary system, though we can’t resolve two stars in the telescope. The fainter blue component, Albireo B, may be only passing by, and not gravitationally interacting with Albireo A at all. Albireo is about 430 light-years away.

Algol (β Persei)

Algol is a famous variable star. The Arabic name, “al Ghul” (related to the English “ghoul”), means “the demon.” It comes from a longer phrase that refers to the demon’s head. In Greek mythology, the star Algol represented the head of Medusa, held up by Perseus’s fist. To the eye, this star appears slightly bluish white. Close observation will reveal an interesting characteristic. Every 2.9 days, the brightness of Algol drops to just 30 percent of normal. The drop in brightness lasts only a few hours. This variation in brightness may be the reason the star was once considered to be unlucky. The cause of the variation in brightness is a stellar eclipse. Algol is a close double star whose components orbit each other every 2.9 days. Its companion is much fainter than Algol itself, but is actually larger in size. When it passes in front of Algol, it eclipses the light of the brighter companion.

Double Double (ε Lyr)

The Double-Double (ε Lyrae) looks like two stars in binoculars, but a good telescope shows that both of these two are themselves binaries. However, there may be as many as ten stars in this system! The distant pairs are about 0.16 light-year apart and take about half a million years to orbit one another. The Double-Double is about 160 light-years from Earth.

Mizar & Alcor

In the handle of the Big Dipper, Mizar & Alcor (ζ & 80 Ursae Majoris) or the “Horse & Rider” form a naked-eye double star. They are traveling through space together about 80 light-years away from us, separated by about a light-year. However, it is unknown if they are actually gravitationally bound to each other. A telescope splits Mizar itself into two stars, but these both are again doubles, bringing the total in this system to six.

Mu Cephei (μ Cep)

Mu Cephei (μ Cephei), also known as Herschels Garnet Star, is a red supergiant star in the constellation Cepheus. It is one of the largest and most luminous stars known in the Milky Way. It appears garnet red and is given the spectral class of M2 Ia. Since 1943, the spectrum of this star has served as one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.

VV Cephei

VV Cephei is a binary star system seen in the constellation Cepheus. As one of the most dramatic variable stars, the brightness appears to change as each star in turn eclipses the other. It takes the 2 stars just over 20 years to orbit each other. The larger of the stars, VV Cephei A is so large that if it were to replace our Sun, its outer edge would lie past the orbit of Jupiter! It is one of the largest known stars.

2.1-Meter Telescope

The 2.1 Meter telescope has an 84″ primary mirror made of Pyrex, that weighs 3,000 lbs. The telescope became operational in 1964—one of the first operational reserach telescopes on the mountain. As part of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) for many decades, it is an important part of the history of the mountain, and has made many important contributions to astronomical research. Despite its significant role within the National Observatory, by 2015 the time came to pass the telescope on to new tenants, so NOAO could focus its efforts on its newer, more advanced telescopes. The Robo-AO team stepped in, and installed their state-of-the-art robotic adaptive optics system on the 2.1 Meter. Adaptive optics allows telescopes to nearly eliminate the distorting effects of the atmosphere, greatly increasing the resolution of the telescope. Thanks to its new tenants, suite of instruments, and the dark skies of Kitt Peak, the 2.1-meter continues to make important contributions to astronomical research.

3.5-Meter WIYN Telescope

The WIYN Observatory is owned and operated by the WIYN Consortium, which consists of the University of Wisconsin, Indiana University, National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO), the University of Missouri, and Purdue University. This partnership between public and private universities and NOAO was the first of its kind. The telescope incorporates many technological breakthroughs including active optics hardware on the back of the primary mirror, which shapes the mirror perfectly, ensuring the telescope is focused precisely. The small, lightweight dome is well ventilated to follow nighttime ambient temperature. Instruments attached to the telescope allow WIYN to gather data and capture vivid astronomical images routinely of sub-arc second quality. The total moving weight of the WIYN telescope and its instruments is 35 tons. WIYN has earned a reputation in particular for its excellent image quality that is now available over a wider field than ever before through the addition of the One Degree Imager optical camera.

90" Bok Telescope

The 90″ (2.3 m) Bok Telescope is the largest telescope operated solely by the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory. The telescope was dedicated on June 23, 1969 and on April 28, 1996 was officially named in honor of Prof. Bart Bok, director of Steward Observatory from 1966-1969. The Bok Telescope is available for use by astronomers from the University of Arizona, Arizona State University, and Northern Arizona University.

Arizona Radio Observatory 12-Meter Telescope

Originally, a 36 foot (11 meter) radio telescope resided in this dome. Built in 1967, the 36 Foot Telescope, as it was known, was a part of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO). In 1984, it was replaced with a slightly larger dish, and the name was changed to the 12 Meter Telescope.

In 2000, the NRAO passed control of the telescope to the University of Arizona. The University of Arizona had been operating the Submillimeter Telescope (SMT) located on Mount Graham since 1992. When it took over operations of the 12m, it created the Arizona Radio Observatory (ARO) which now runs both telescopes.

In 2013, the telescope was replaced with ESO’s ALMA prototype antenna. The new dish is the same size, but has a much better surface accuracy (thereby permitting use at shorter wavelengths), and a more precise mount with better pointing accuracy. The 12m Radio Telescope is used to study molecules in space through the use of molecular spectroscopy at millimeter wavelengths. Many of the molecules that have been discovered in the interstellar medium were discovered by the 12m.

Calypso

Though the Calypso telescope and its 1.2 meter mirror have now been acquired by the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope team, it once occupied the large “garage on stilts” on the west side of the mountain. Edgar O. Smith, a businessman-turned-astrophysicist, designed Kitt Peak’s only privately owned telescope to create the sharpest possible images. The garage-like building rolls away on rails, leaving the telescope very exposed, and able to cool to ambient temperature. Its adaptive optics system can adjust 1,000 times per second to remove atmospheric blurring. Calypso will eventually be moved to Cerro Pachón in the Atacama Desert of Chile. The “garage on stilts” sits empty.

Kitt Peak VLBA Dish

The Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) is a part of the Long Baseline Observatory (LBO). It consists of a single radio telescope made up of ten 25 meter dishes. The ten dishes are spread across the United States, from Hawaii to the Virgin Islands. One dish is located on Kitt Peak: The LBO Kitt Peak Station. Kitt Peak Station, along with the other dishes, work in unison to point at the same targets at the same time. The data is recorded and later combined. By spreading the dishes out over such a great distance, instead of building them all in the same place, a much higher resolution is gained.

Mayall 4-Meter Telescope

The Mayall 4 Meter Telescope was, at the time it was built, one of the largest telescopes in the world. Today, its mirror—which weighs 15 tons—is relatively small next to the mirrors of the world’s largest telescopes. Completed in the mid-’70s, the telescope is housed in an 18-story tall dome, which is designed to withstand hurricane force winds. A blue equatorial horseshoe mount helps the telescope point and track the sky. A new instrument called DESI (Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument) will soon be installed on the 4-meter. Once installed, DESI will take spectra of millions of the most distant galaxies and quasars, which astronomers will use to study the effect of dark energy on the expansion of the universe.

The Mayall 4 Meter is named for Nicholas U. Mayall, a former director of Kitt Peak National Observatory who oversaw the building of the telescope.

McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope

The Mc Math Pierce Solar Telescope is actually 3 telescopes-in-one. It was, at the time of its completion in the 1960s, the largest solar telescope in the world. It will remain the largest until the completion of the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) in 2018. The Solar Telescope building looks like a large number 7 rotated onto its side. The vertical tower holds up 3 flat mirrors, which reflect sunlight down the diagonal shaft—a tunnel which extends 200 feet to the ground, and another 300 feet below ground, into the mountain. At the bottom of this tunnel are the three curved primary mirrors, which reflect the light of the Sun back up to about ground level, where the Sun comes into focus in the observing room.

MDM Observatory

MDM Observatory is located on a lower ridge to the southwest of the main observatory campus. Its name comes from its original member universities—University of Michigan, Dartmouth and MIT. Current members of the observatory are University of Michigan, Dartmouth, Columbia, Ohio State University, and Ohio University. MDM consists of two telescopes—the McGraw Hill 1.3 meter and the Hiltner 2.4 meter.

SARA 0.9-Meter Telescope

SARA stands for Southeastern Association for Research in Astronomy. Formed in 1989, SARA sought to form a mutually beneficial association of institutions of higher education in the southeastern United States which have relatively small departments of astronomy and physics. At the time, a 36″ telescope on Kitt Peak was being decommissioned by the National Observatory. The Observatory planned to award the telescope to new tenants who showed they could use the telescope well. SARA’s proposal for use of the telescope was selected out of about 30. Today, SARA operates the 0.9 meter telescope of Kitt Peak, as well as a 0.6 meter telescope at Cerro Tololo in Chile. Both telescopes can, and are mostly used remotely.

The RCT

The Robotically-Controlled Telescope (RCT) is a 1.3-meter telescope on a German equatorial mount. The RCT occupies the dome across from the Kitt Peak Visitor Center. The long building attached to the RCT dome is the Kitt Peak administration building. The RCT name originally stood for Remotely-Controlled Telescope, and it served the KPNO user community almost 30 years before being closed in 1995. The telescope was originally proposed by the Space Sciences Division at KPNO as the Remote Control Telescope System (RCTS) to be an engineering research platform for the development of remote control protocols for envisioned orbital telescopes. In later years, the telescope was used to test out various instrumentation that was later used on the larger 2.1-meter and 4-meter telescopes of Kitt Peak. In 2004 The RCT Consortium began operating the telescope as its new tenants. Today, the telescope is mostly used either remotely, with observers operating the telescope via the internet, or robotically, with the telescope opening and observing automatically, using its programming to determine what to observe based on scheduling and observing conditions.

Your Telescope Operator and Guide. Thank you for joining me this evening! See you soon!!

The web page for the program in which you just participated is at

Nightly Observing Program. Most of the above images were taken as

part of

the Overnight Telescope Observing Program. For more information on this unique experience please visit Overnight Telescope Observing Program.

Copyright © 2019 Kitt Peak Visitor Center

Leave a comment